Not your garden variety Petunia, this petunia carries artist's DNA

In "Edunia," now on display at the Weisman Art Museum, Eduardo Kac shows links among living things.

By Mary Abbe

The ever-accelerating March of Science has brought us cloned sheep, cows and most recently a camel. Are we ready now for a "plantimal"? That is, a creature combining genetic material from a plant and an animal? Specifically a petunia infused with human DNA?

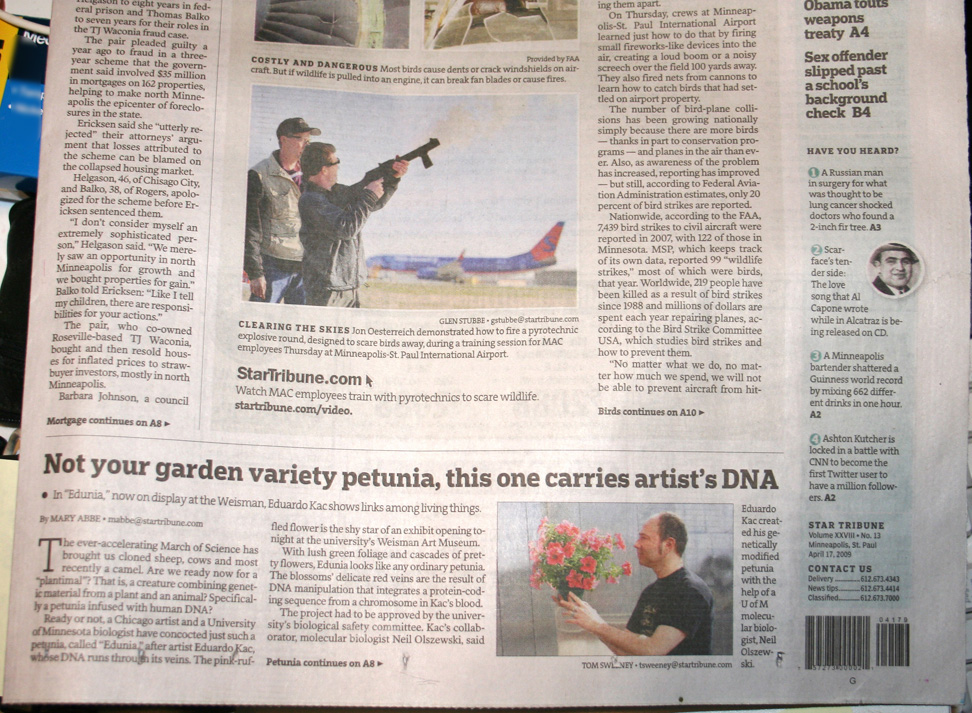

Ready or not, a Chicago artist and a University of Minnesota biologist have concocted just such a petunia, called "Edunia," after artist Eduardo Kac, whose DNA runs through its veins. The pink-ruffled flower is the shy star of an exhibit opening tonight at the university's Weisman Art Museum.

With lush green foliage and cascades of pretty flowers, Edunia looks like any ordinary petunia. The blossoms' delicate red veins are the result of DNA manipulation that integrates a protein-coding sequence from a chromosome in Kac's blood.

The project had to be approved by the university's biological safety committee. Kac's collaborator, molecular biologist Neil Olszewski, said the idea initially caused a stir among some faculty, who worried that the project could be a "lightning rod for protesters." Others feared that applying DNA research in art might lead to ridicule.

"Some people are just opposed to what they call 'man playing god,' taking DNA from humans and putting it into a plant," Olszewski said. "They say it's unnatural and shouldn't happen."

The biologist disagreed, saying that such arguments do not give nature "due credit" for situations in which "DNA does in fact move across species boundaries," such as the nasty tumors that bacteria commonly cause in roses.

A professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Kac, 46, is internationally known for his work in technology and bio-art. His most famous creation was Alba, a genetically modified white rabbit whose fur glowed green because of an infusion of fluorescent jellyfish genes.

For Kac (pronounced "cats"), the similaritybetween the vascular systems of plantsand animals is a potent metaphor.People generally accept theirfundamental similarity to animals, but"the thought that we are also close to other life forms, including flora, will strike most as surprising," he writes on hiswebsite, www.ekac.org.

Or, as he put it this week at the Weisman, "I'm hoping people will realize this is no plastic flower we're talking about; it's a living being just like me."

Despite its novelty, Edunia is probably not the first mingling of plant and human DNA said Olszewski. When Kac proposed the project to a group of university scientists about five years ago, Olszewski was intrigued because of his own earlier research on plant vascular systems and his admiration for a Kac work shown at the Weisman in 2004. In the earlier piece Kac translated a biblical text from Genesis into Morse Code and then into a DNA sequence, which produced a novel strain of bacteria that viewers could mutate by zapping it with ultraviolet light.

"I was blown away by that Genesis piece because it explores so many philosophical issues," said Olszewski. "He's encoded Genesis into the DNA, and if you believe in man's dominion over life, how more can you dominate something than by turning on that light and mutating the DNA?"

Kac's photos, drawings and installations are in the collections of New York's Museum of Modern Art, Chicago's Holography Museum and the Modern Art Museum of Rio de Janeiro, his hometown.

The university also commissioned a Kac sculpture inspired by the petunia's DNA that is permanently installed on the St. Paul campus outside the Cargill Center for Microbial and Plant Genomics. The $65,000 fiberglass-and-steel work was paid for by a state-funded program.

Like all research involving the creation of transgenic organisms, Edunia had to be approved by the university's biological safety committee and conform to guidelines issued by the National Institutes of Health. That means, among other things, that no leaves, seeds or blossoms escape into the natural environment. Ultimately Edunia will be destroyed, though some of its seeds will become part of the Weisman's permanent collection.

"There is really nothing to be concerned about with this plant," Olszewski said. "Even it if got out, it wouldn't do anything in the environment and does not represent any kind of risk. ... It achieves Eduardo's artistic gesture, but there are no bio-safety concerns."

|  |

Back to Kac Web